- I frequently get so strongly absorbed in one thing that I lose sight of other things.

- I tend to notice details that others do not.

- I would rather go to a library than a party.

- I tend to have very strong interests which I get upset about if I can't pursue.

- I frequently find that I don't know how to keep a conversation going.

- I find it difficult to work out what someone is thinking or feeling just by looking at their face.

- People often tell me that I keep going on and on about the same thing.

- New situations make me anxious.

- When I listen to a piece of music, I always notice the way it's constructed

- In maths, I am intrigued by the rules and patterns governing numbers.

- When I read something, I always notice whether it is grammatically correct.

- I find it difficult to explain to others things that I understand easily, when they don't understand it the first time.

- Friendships and relationships are just too difficult, so I tend not to bother with them. (Wheelwright et al., 2006)

These statements are familiar to many people. Some people recognise these things in themselves, or in family, students or co-workers. They might be obvious or subtle, alone or in combination. These are some of the ways that cognitive traits associated with high-functioning autism and Asperger's Syndrome can manifest and the statements are adapted from some of the diagnostic assessment tools used by psychologists to identify the conditions.

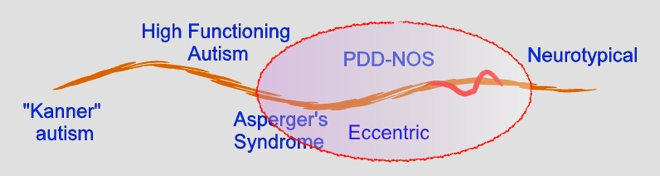

The terms autism, autistic, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Asperger's Syndrome (AS) are used in this document and they represent a group of related developmental disorders of the brain often referred to collectively as the Autism Spectrum of Disorders, indicating a variance of severity and specific traits. Like the spectrum of light, there is overlap between the various member of the group, but unlike light, there is also considerable variance within each member.

The term Autism also refers to the entire range of disorders and traits under discussion, but it is commonly used to describe to the lower functioning end of the Autistic Spectrum where an intellectual impairment is also indicated. The word is sometimes claimed by members of the Asperger and High Functioning Autism community as a badge of honour. In this document, autistic describes an individual with a diagnosis anywhere along the spectrum of disorders from Kanner Autism to Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS). Asperger's Syndrome is a specific condition that is a form of High Functioning Autism (HFA - indicating no intellectual impairment) without spoken language delay. There is currently debate around whether Asperger's Syndrome is different enough from HFA to maintain its place in the forthcoming version five of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (Ghaziuddin, 2010). There is currently debate around whether Asperger's Syndrome is different enough from HFA to maintain its place in the forthcoming version five of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (Ghaziuddin, 2010). The two are currently differentiated by there being no spoken language delay in Asperger's Syndrome. PDD-NOS is the least understood aspect of the spectrum and is also on the review list for the DSM-V. It is effectively a diagnosis by exclusion - the individual is clearly affected by the social and other symptoms of autism, but not in the configuration by which the other diagnoses are made.

The diagram below gives an indication of the disorders "on the spectrum". While this suggests a linear progression with the "worst case" of Kanner Autism at one extreme and normality at the other, the reality is somewhat more complicated. While Asperger's Syndrome is sometimes described as the "bridge between normal and autistic" (Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin & Clubley, 2001, p. 8), it is not a "mild form of autism" as many recent media reports would have us believe, but a specific form that can have significant impact on the individual and those around them. The term High Functioning Autism normally refers to a lack of intellectual impairment, function is an ambivalent concept, and individuals diagnosed with HFA or Asperger's may be severely impacted in terms of social function.

The etymology of the word autism comes from the Greek "auto" meaning self, and was first used by Leo Kanner in 1943 (Kanner, 1943) to describe a particular set of characteristics, an "autistic psychopathology" that included an intellectual impairment. In the following year, Hans Asperger (1944) independently described children with similar characteristics but without an intellectual impairment. While Kanner's article (1943) was published in English and widely received, Asperger's German language publication received little attention until it was discussed in English in 1981 by Lorna Wing (1981). Wing made a distinction between different types or manifestations of the autistic disorder and the particular collection of traits described by Asperger was attributed to him. Scott (1985) and Gillberg (1987) also used the term Asperger's Syndrome and Gillberg developed a diagnostic criteria. This criteria was later supplemented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and additional tools of diagnosis are now used in various countries. The arguments about different forms of autism and how to diagnose them have continued over the years and there is still debate over how the distinctions will be defined in the DSM-V.

Autistic Spectrum Disorders are now being recognised more consistently and at an earlier age in children, with recent studies indicating rates between thirty and seventy per 10,000 (Fombonne, 2001; Fombonne, 2009; Lenoir et al., 2009; VanDenHeuvel, Fitzgerald, Greiner & Perry, 2007; Williams, MacDermott, Ridley, Glasson & Wray, 2008). However, ASDs are more difficult to diagnose in adults and adolescents due to the individual learning to "pretend to be normal" over time (Stoddart, 2005, p. 13; Willey, 1999).

ASD involves a triad of impairments,

- disturbance of reciprocal social interaction,

- disturbance of communication, and

- restriction of normal variation in behaviour and interests.

These aspects are dealt with in greater detail in other sections of this document, but can be interpreted as affecting social skills, non-verbal communication, empathy, executive function and central coherence (Stoddart, 2005, pp. 14-16). One aspect that is not a part of the DSM-IV criteria, but has been a known but little understood aspect of the autistic profile for many years (Eaves, Ho & Eaves, 1994) is differences or disturbance in sensory perception and regulation. There are current calls for this to be addressed in all diagnostic criteria and for further research.

As the list of statements that begin this section indicate, traits associated with Autistic Spectrum Disorders - so-called autistic traits - occur commonly in the general community (Constantino & Todd, 2003, p. 524) and may be of great value to the individual (Gray & Attwood, 1999). Individuals with Asperger's Syndrome have a collection of autistic traits that do not include intellectual impairment or speech delay, and in fact, strong predominance of certain characteristics may make them well suited to particular pursuits including academic research, science, mathematics and creative professions where systems and lateral thinking are useful, such as music, acting and visual arts. We all know people who are very focussed or poor communicators for example, and generally they get along fine, but when sufficiently marked, the traits can cause significant impairment of day-to-day functioning and be recognised through a diagnosis on the spectrum.

Autism is pervasive; it does not respond to medication and get better in the way a mental illness can do. However, individuals can and do learn to manage some of the traits and control them so that they may be less obtrusive, and some autistic or co-morbid symptoms such as anxiety, depression or ticcing can be improved with medications. In addition, the autistic conditions are syndromes - a collection of traits and symptoms - independent of personality. The result is individuals who are just as unique as non-autistic persons, but with a profile of a particular flavour. That flavour can be seen in small amounts in many people. There is no such thing as someone who is purely autistic or purely non-autistic. As Jerry Newport, author of Mozart and the Whale writes, "Even God had some Autistic moments, which is why the planets all spin" (Newport, Newport & Dodd, 2007).

Related Posts

- ASD and Asperger's Literature: A brief overview of the major literature on Asperger's Syndrome

- Context: "Experience ... derives its validity from the conditions and context of consciousness in which it arises"

- Statistics: Information on prevalence and distribution of ASD in the community.

- Thematic Analysis: Thematic analysis underpins the process of drawing insight from the narrative and media based data.

- Speaking, Hearing, Seeing: People with Asperger's and HFA often have unusual ways of speaking, hearing and seeing interpersonal communication modes.

- The Diagnosis: How Asperger's Syndrome is diagnosed.

- Criteria for Diagnosis of Asperger's Syndrome: The American Psychological Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - version IV and Gillberg criteria for Asperger's Syndrome.